Wallenstein Palace in Prague – The Seat of the Senate

| Address: | Senát Parlamentu ČR, Valdštejnské nám. 17/4, 118 01 Praha 1 – Malá Strana |

|---|---|

| Description of work: | Restoration of stone elements Restoration of bronze sculptures in the garden of the complex Restoration of wall frescoes |

| Contractor: | GEMA ART GROUP a.s. |

| Investor: | Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic |

| Implementation: | 1996-2001 |

Wallenstein Palace in Prague is an extensive architectural complex built in the style of Early Baroque Italian urban residences. The eponymous palace was commissioned by Albrecht Wenceslas Eusebius von Wallenstein (1583–1634). This Czech general and politician was one of the most influential men of his time in Europe and featured significantly in the history of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). Thanks to his military talent and intelligence the highly ambitious Wallenstein reached the rank of generalissimo in the Imperial army at the age of 42.

His standing and influence were showcased in his grandiose estates. His original properties in Friedland (Frýdland) district expanded to eventually encompass almost all of north-eastern and eastern Bohemia. The area was in 1627 elevated to the status of Duchy of Friendland with the town of Jičín as its centre. Wallenstein intended to turn the duchy into his own state of sorts, with a university, assembly and bishopric.

He also desired to establish an imposing residence in Prague, which could in size and appearance compete with Prague Castle. He took the first steps towards this ambition in 1621, a year after the Battle of White Mountain, when his power and influence grew thanks to support from the victorious Emperor Ferdinand II. Over time he purchased 26 properties in the Lesser Town, including the large Trčkov Palace from the 13th century.

The actual building work commenced in July 1623 and several renowned architects and artists from Italy participated in the project. Among the chief architects were Andrea Spezzo (1580–1629), Boccaccio Vincenzo (1585–1643) and Nicolo Sebregondi (1585–1652).

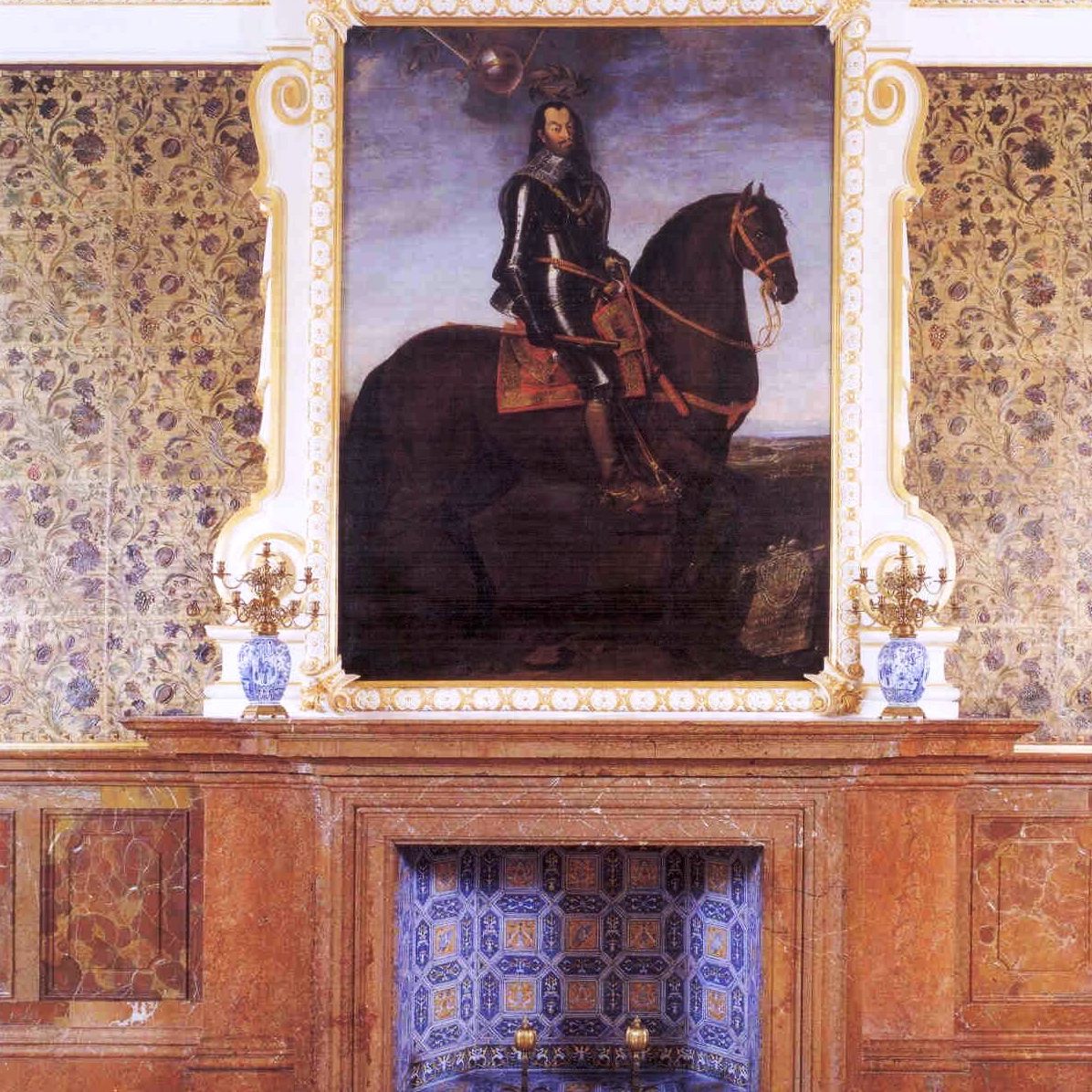

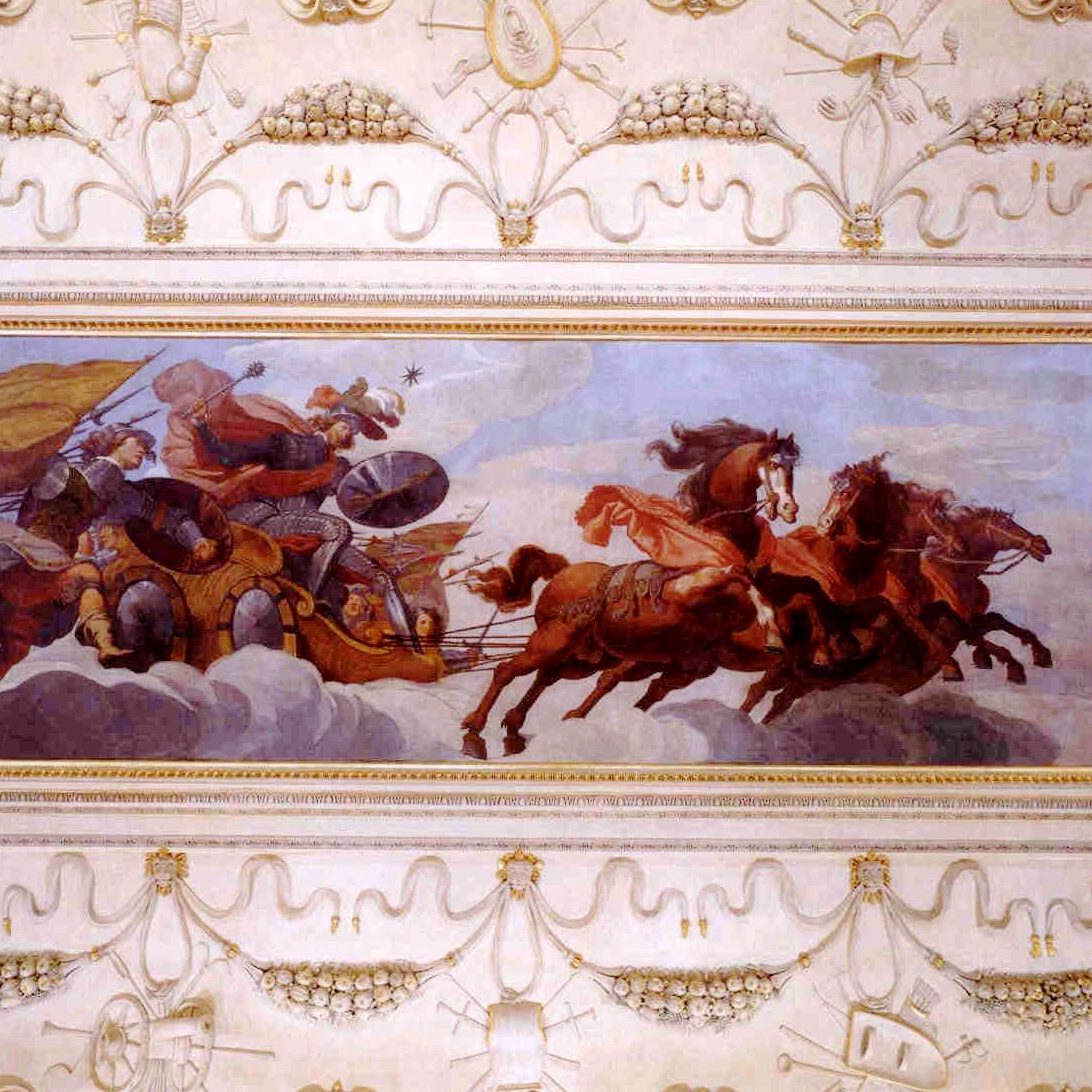

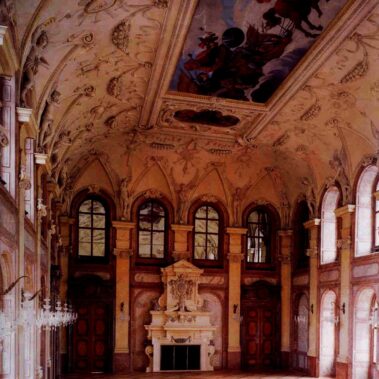

The residence comprised several buildings and courtyards. Apart from the living quarters the complex had a page quarter, accommodation and offices for the estate’s managers and staff, stabling for horses and a riding courtyard with winter riding stables. The most imposing parts of the complex were without doubt the duke’s living quarters. They had two kitchens, a private chapel with a wall fresco illustrating the lives of the Virgin Mary and St Wenceslas; the Přemyslid Prince is portrayed here as an army leader. The residence had a magnificent piano nobile with a Hall of the Knights, dominated by a ceiling painting of Albrecht of Wallenstein depicted as the God Mars in his chariot, an Audience Hall featuring splendid vaulting decorated with frescoes of the Four Ages of Man and Forge of Vulcans in the centre. The duke’s private chambers comprised an office, bedroom, closet, dressing room and dining room. A discreet spiral staircase connected Albrecht’s bedroom to the private accommodation of his wife, Isabella Catherine Countess of Harrach. The rooms of their daughter Maria Elizabeth were also located in this part of the palace.

The décor of the palace was inspired by North Italian influences. Their typical mark are ornamental stuccoes outlining the areas of the frescoes. The iconography of the frescoes had four main themes: war, religion, Greek and Roman mythology and astronomy. The majority of the frescoes was created by Bartolomeo Baccio del Bianco (1604–1656), the stuccoes were the work of Domenico Canevalle and Santino Galli. The carvings in the Chapel of St Wenceslas were made by Ernst Johann Heidelberg, the artisan carver at the court of Ferdinand II.

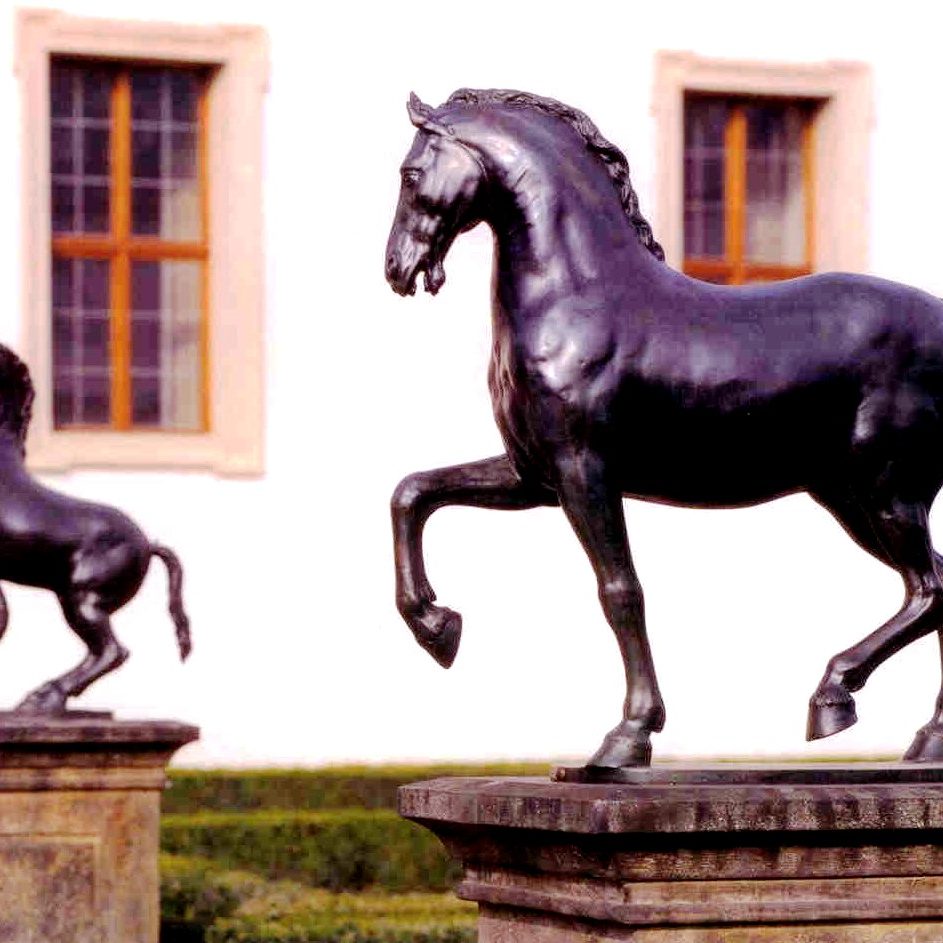

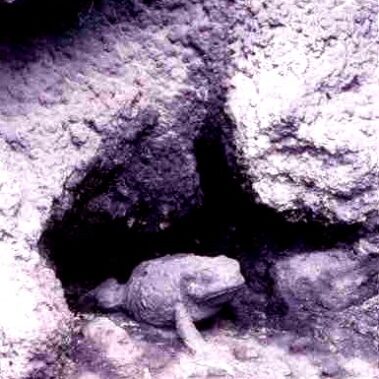

Right from the beginning the Wallenstein Garden, which covers two thirds of the whole area of the complex, attracted most of the attention. The garden was divided into three thematic parts. The sala terrena, or logia, was the venue for summer festivities and was ornamented with statuary and several frescoes separated by stucco decorations. Individual frescoes depicted Homer’s story of the Trojan war. The architect of this monumental ground floor logia was Giovanni Battista Pieroni. Side by side with the sala terrena was the so-called “giardino segreto”, or secret garden, a favourite feature of the Italian Renaissance. This part of the gardens had a thick planting of trees, grottos, aviary and a wall with an artificial rock face. The dark grey wall bore images of toads, snakes and frightening gargoyle faces, all of which created an oppressive atmosphere. This dark area was counterbalanced by another garden with a large pond, which to this day creates a “mirror” for the architecture of the palace. The garden was decorated with bronze statues, work of the Dutch sculptor Adrian de Vries (1545–1626). The statues were stolen by the Swedish army during the Thirty Years’ War on the order of Queen Christina (1626–1689). Identical casts of the statues were manufactured in the years 1913 to 1918. The originals are now held in Swedish Drottningholm.

The Wallenstein Palace was completed early in the 1630s but the Duke of Friedland himself was unable to make much use of it. Decline of his health acerbated by syphilis affected his mental state and his often nonsensical decisions put a stop to his high-flying military career. His enemies took advantage of this and denounced him as an arch traitor at the Imperial court. On orders from the Emperor the duke was murdered in his house in the town of Cheb in February 1634.

Most of his property was confiscated. His widow Isabella and daughter Elizabeth von Wallenstein were only allowed to keep the Wallenstein Palace and an estate in the town of Česká Lípa. Members of the Wallenstein family inhabited the palace until the end of World War I. The situation changed after 1919, when Adolf von Wallenstein rented the complex to the Ministry of Industry and the riding stables to automobile manufacturer Laurin and Klement. After the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia the complex was used by the Ministry of Culture and Adult Education, led by the collaborator Emanuel Moravec.

After 1945 the palace was nationalized and its premises used by the Ministry of Culture, the National Gallery and the Comenius Pedagogical Museum.

The decision to designate the Wallenstein Palace the seat of the Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic was taken at the beginning of 1996. The extensive reconstruction, including delicate restoration work, was carried out between the years 1996 and 2001.

Source:

Collective of authors. Valdštejnský palác v Praze. Praha: GEMA ART, 2002, 517 pp.

Restoration work carried out in the Wallenstein Palace represented one of the most extensive commissions realized within a tight schedule in the history of the GEMA ART GROUP a. s. company. The aim of the project, which was managed by GEMA ART GROUP a. s., was the preservation of historically valuable features and remedial work on unsuitable and damaging restoration interventions carried out in the past.

As is customary any actual work was preceded by necessary surveys, which varied in scope and character. The information gathered was evaluated and a restoration blueprint was drafted. In the course of the restoration work this blueprint was continually re-evaluated and re-adjusted as required.

The tasks included restoration of stucco, frescoes and stone elements, repairs to the ornamental wall of the grotto, artificial marbles in the interior, bronze replicas of Adrian de Vries sculptures and restoration of leather wall coverings.

The desired outcome of the project was to rediscover the decorative components of the palace as integral parts of an artistic and artisan whole, which belongs to peak examples of European Early Baroque architecture. The high quality of the execution of the task was acknowledged by the EU, who awarded the project the Europa Nostra prize in the category “Architectural Heritage” for its complex approach to restoration and reconstruction of the palace.

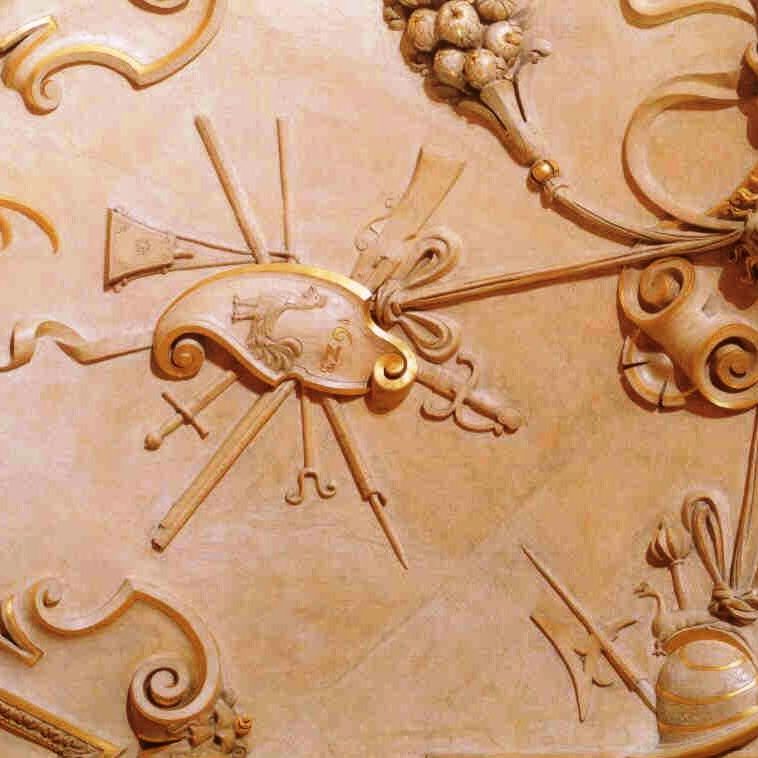

Restoration of stucco decorations:

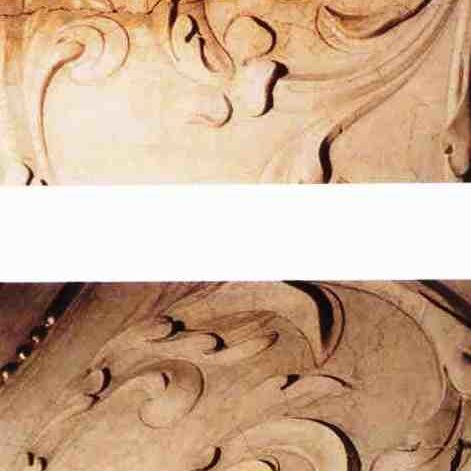

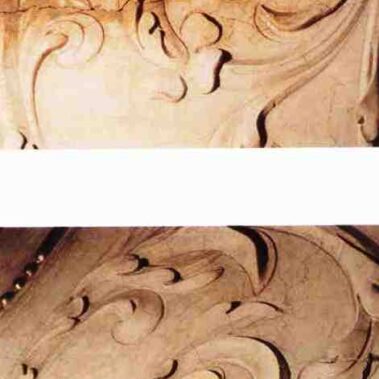

The restoration involved the original stuccoes from the 17th century as well as the later stucco decorations from the 18th and 19th century. Extensive repairs to the stuccoes had already been carried out during the 19th century and later on in the middle of the 20th century.

The majority of the original stuccoes is located in the Chapel of St Wenceslas, in the main hall and in the Mythology and Astronomy and Astrology corridors. The stuccoes have the form of egg and dart, astragals, mascaroons, winged female torsos, scrolls and various floral bands. Stucco decorations from the 18th century are mostly found in the Mirror Hall and consist of floral and vegetative motifs with petite figures. The newest stucco ornamentation, which dates from the 19th century, is in the Hall of the Knights and comprises mostly profiled features such as ledges, dentils, egg and dart and stylized leaf, all of which were produced by casting from moulds.

To start with, geo-chemical and petrologic analysis of the plastering layers was carried out. A restoration blueprint for each individual artwork was created, bearing in mind the overall unity of the building’s appearance.

The stucco ornamentation exhibited instances of damage such as cracks, broken off parts and in places the occurrence of laitance.

The stuccoes were first thoroughly cleaned of dust deposits using tenzide fluid combined with steam, avoiding any abrasive treatment. Residues of wax and oil were removed with chemical solvents. Deep cracks were injected with consolidants and sealed. Broken off parts of floral motifs from the 18th century were replace by copies. Loose parts were secured by screws inserted into underlying boards. To conclude the stuccoes were retouched and coated in a protective conservation agent.

Different materials were used in the restoration of the stuccoes from the 19th century, whose composition was dissimilar to that of the older ones. The stuccoes were damaged to a significant degree when the palace central heating pipes burst. Once the original appearance of the stuccoes was established repairs were carried out followed by conservation using diluted varnish.

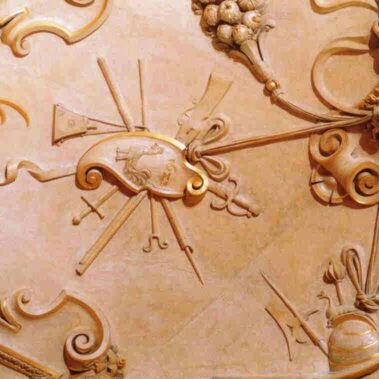

Restoration work connected with the golding of the stuccoes:

Prior to restoration a survey was carried out and a row of probes inserted. The aim of these procedures was to establish the extent and state of the original gilding, which was painted over during later repairs; conversely, in places new gilding was applied where none existed originally. The original gilding was of high purity, up to 89%. After evaluating all the factors the restorers decided to respect the extent of the gilding as preserved from the last previous restoration.

During the restoration work it became necessary to eliminate the darkened retouching, applied during the previous renovation. After the removal of the blackened bronzing the surfaces were retouched with shellac, mixtion base was applied and gold leaf laid. To conclude the new gilding was colour harmonized with the original.

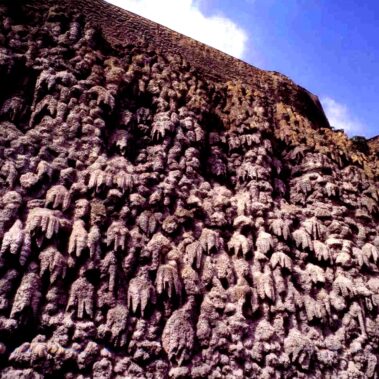

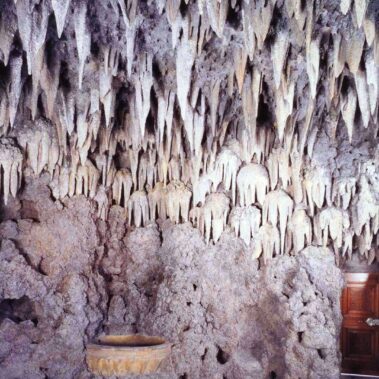

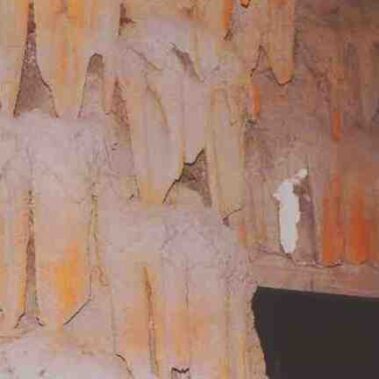

Restoration of the man-made stalactite wall of the grotto:

No written mention about previous repairs was found and it is possible that no records were made. Nevertheless it has been clearly established from the restoration surveys and archive photographs that partial repairs of the wall had taken place.

The material from which the grotto wall was made exhibited many instances of damage. During the previous unprofessional repairs non-porous cement was used and moisture condensed under this impermeable layer; temperature fluctuations subsequently caused cracks and breakage. Signs of pollution were most pronounced in the lower part of the wall and in the cavities of the stalactites.

The surfaces were cleaned using regulated steam and then injected with polymer consolidants designed to strengthen the outer layers. To conclude colour retouching was carried out using iron pigments and titanium white.

Restoration of stone elements:

Restoration of stone elements concerned both the exterior and the interior of the palace. It involved mostly restoration of stone basins, sculptures and architectonic elements of the Wallenstein Palace buildings. Originally the palace paving was also made of stone, namely Žehrovice arkose sandstone, but it only survived to any extent within the sala terrena.

At the start of the restoration the stone was cleaned using regulated steam. To follow any missing parts were replaced by copies manufactured from artificial stone. All elements were comprehensively conserved, retouched and colour harmonized with their surrounding.

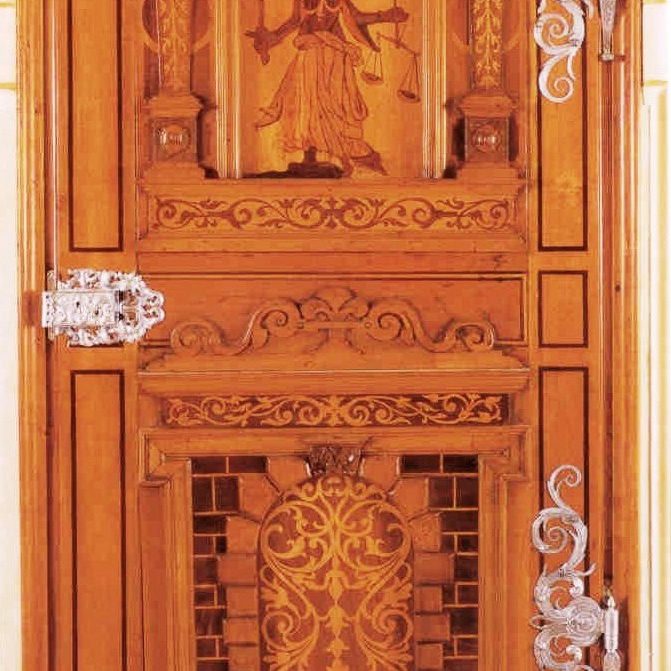

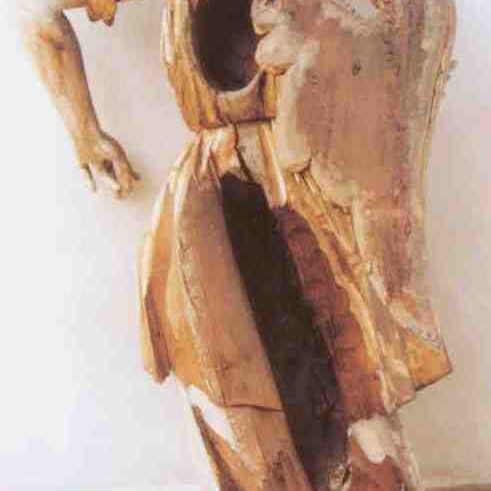

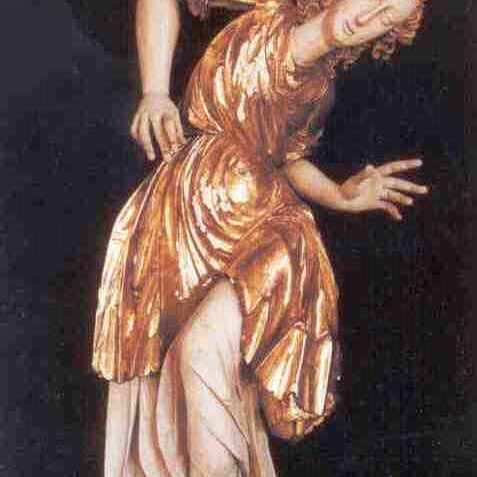

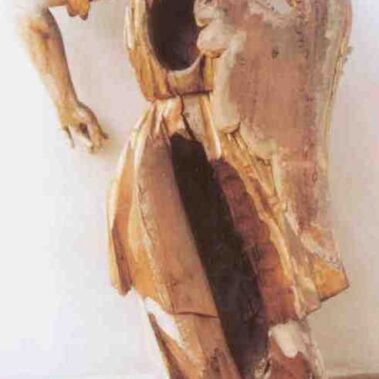

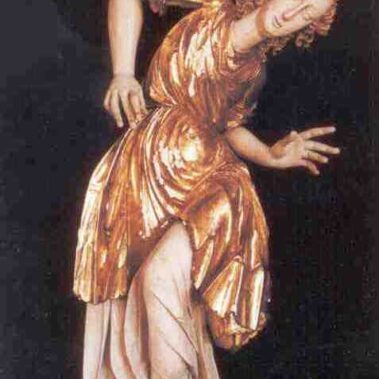

Restoration of the wooden statues from the altar of the Chapel of St Wenceslas:

Restoration work here involved individual wooden statues as well as other items of altar architecture such as angels, a figure of St Wenceslas, carved ribbons and urns and helical columns draped in vines. All woodcarvings were the work of renowned artisan carver Ernst Johann Heidelberg.

The sculptures imitated the style of the so-called chryselephantine of Ancient Greece, but instead of ivory polished wood and gilding were used. The statuary of the altar was in a dilapidated state, in particular the putti exhibited deep fissures and darkened old retouches were crumbling away.

Once the dust deposits were removed the white chalk layer was strengthened and dark bronze retouches and any unsuitable fillers were removed. In areas where the chalk base was altogether missing a new one was applied. To follow, re-gilding with gold leaf was carried out. To conclude all surfaces were polished and treated with beeswax emulsion.

Restoration of the artificial marbles:

Artificial marbles were used in the main hall and in the Mythology corridor, where they formed a row of coloured pilasters. The marble cladding is a later addition and was put in place in the years between 1851 and 1865 by two Italian artisan craftsmen Filipe and Giovanni Pellegrini. The artificial marbles were manufactured from smooth gesso mass with the addition of glue and colour pigment.

The marbles have already been renovated several times in the past, most recently in the 1960s and 1970s. Surfaces were well preserved, only the lower parts showed numerous instances of mechanical damage. After residual waxes and oils were cleaned away the cracks were sealed.

The fillers were very carefully selected in order to resemble as closely as possible the remaining original marbles. Once the sealants hardened they were repeatedly smoothed down. Surfaces were then impregnated with a mixture of turpentine oil and beeswax and afterwards carefully polished.

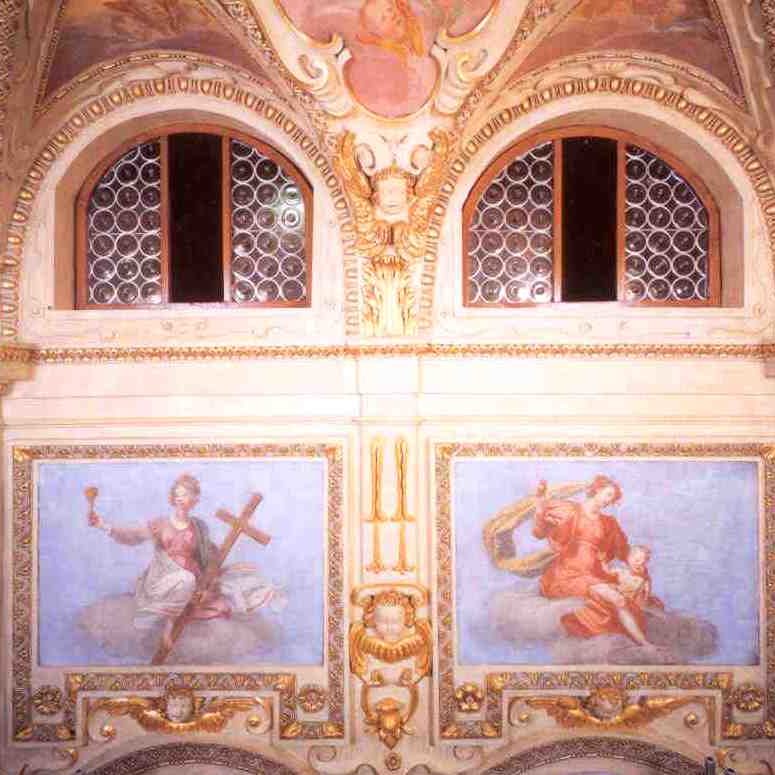

Restoration of the frescoes:

Among the historically most valuable frescoes in the premises of Wallenstein Palace is undoubtedly the “Apotheosis of Albrecht of Wallenstein” in the main hall, which depicts the mighty duke as Mars, the Roman god of war, in a full suit of armour and was modelled on the 1614 fresco in the Palazzo Pallavicini Rospigliosi in Rome. Other important frescoes are situated in the Chapel of St Wenceslas; they illustrate scenes from the life of Prince Wenceslas, such as the paying of homage to the newly elected Prince, building of the Church of St Vitus, the meeting of the Prince with the Roman Emperor and finally the murder of the Prince, the future St Wenceslas. The frescoes in the oratory of the Duchess have scenes from life of the Virgin Mary while the Duke’s oratory is decorated with depictions of the ordeal of the Italian bishop St Eusebius. Frescoes in the centre of the Audience Hall vaulting portray Vulcan’s Forge – that is the Roman god of fire and his wife Venus, goddess of love and beauty and also the Allegory of the Four Times of the Day. The frescoes in the Mythology corridor were inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Individual scenes illustrate Creation of the World, The Fall of Icarus and Medusa Killed by Perseus. The Astronomy and Astrology corridor is decorated with paintings of planets Saturn, Jupiter, Mars and Mercury as well as other celestial bodies such as the sun and the moon, portrayals of four seasons and by the 12 signs of the zodiac.

Repairs to the frescoes were carried out many times in the past. The first intervention of note was the work of the painter and restorer Josef Navrátil in the 1950s.

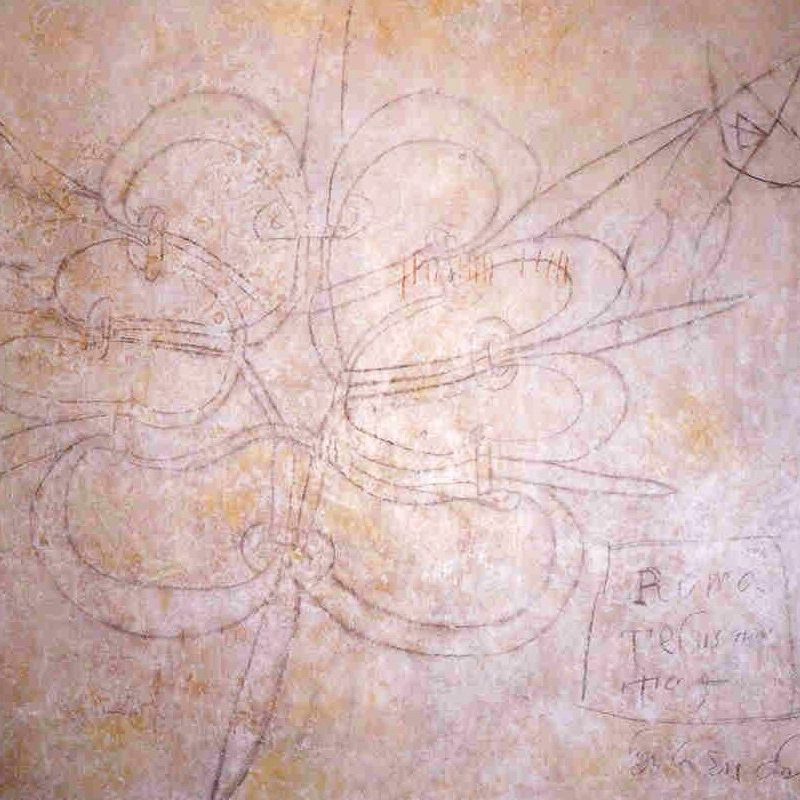

Restoration undertaken in the year 2000 had as its main aim the reconstruction of techniques which would have been used when the frescoes were created. To achieve this, the restoration was preceded by investigations such as colour stratigraphy, chemical analysis and examinations under infrared and ultraviolet light. These surveys established that several frescoes had undergone repainting of extensive parts of many scenes.

The surfaces of the frescoes were powdery and cracked and a film of dust deposits adhered to them. Most damaged were the frescoes in the oratories of the Chapel of St Wenceslas.

Once the dirt, the unsuitable retouching and old egg emulsion fixatives were removed, the cracks were sealed, severely affected areas injected in depth, the frescoes were retouched and cleaned once more.

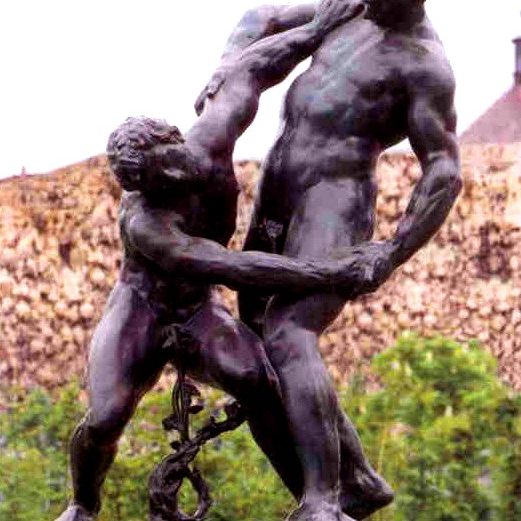

Restoration of bronze statues in the garden:

These are the imitations of the original statues by Adrian de Vries, which were stolen by the Swedish Army during the Thirty Years’ War. The copies were cast in the years between 1913 to 1918 on order of Karl Ernst Wallenstein.

Samples from the statues were taken during the restoration survey. Chemical analysis found no presence of aggressive particles on the surface, which would have caused deep destruction to the bronze. The layer of dirt and localized crusts were carefully mechanically thinned and the surface was then preserved using micro static wax.

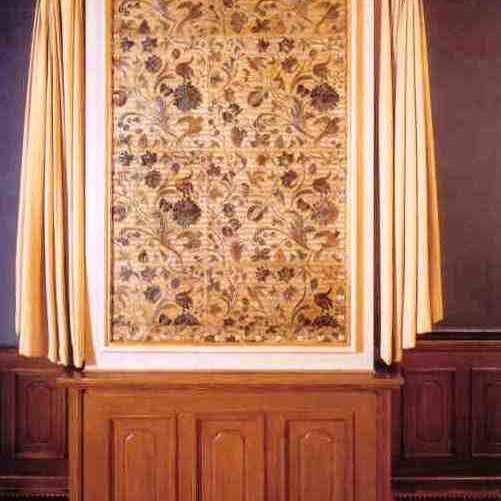

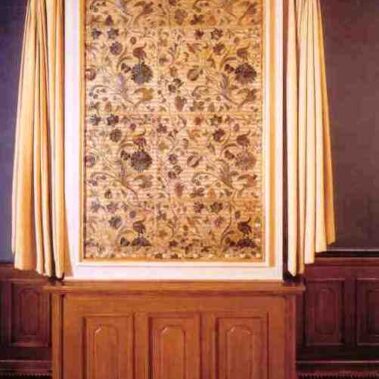

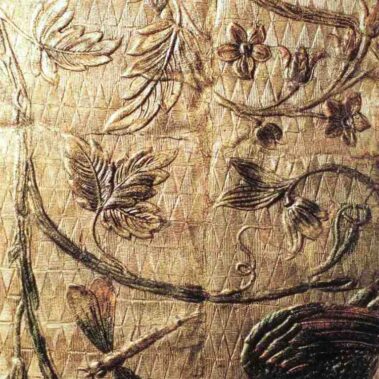

Restoration of historical leather wall coverings:

The wall coverings were installed in 1877. They were imported from Paris and put on the walls by Prague upholsterer Josef Pánek. They were manufactured from horse hide and embossed with decorative motifs of flowers, leaves, fruit, birds and insects. They were extensively repaired on a previous occasion in 1978.

The restoration survey concentrated on the precise identification of the materials and degree of degradation. It found high levels of damage to the leather, dirt, cracking and localized abrasions.

Mechanical cleaning was carried out with utmost caution using special purus rollers and soft brushes. Damaged parts were locally consolidated and backed with new leather. The gilded background was then coloured and retouched using specialist bronze. In order to preserve the wall coverings for the future the experts recommended the stabilization of climactic conditions at temperatures between 18 to 21˚C and a relative humidity of 55%.

Rozsáhlé informace o historii Valdštejnského paláce, minulých opravách a rekonstrukci z let 1996 až 2001 lze nalézt v odborné monografii Valdštejnský palác v Praze, kterou vydalo nakladatelství GEMA ART GROUP. Knihu lze zakoupit za 1255 Kč, blíže na webových stránkách Galerie GEMA:

http://www.gemagalerie.cz/cs/publikace/31-valdstejnsky-palac-v-praze

Otevírací doba Valdštejnského paláce:

duben – říjen: 10:00 – 17:00 (so-ne)

červen-září: 10:00 – 18:00 (so-ne)

listopad-březen: 10:00 – 16:00 (první víkend v měsíci)

Otevírací doba Valdštejnské zahrady:

duben-říjen:

7:30 – 19:00 (po-ne)

10:00 – 19:00 (so-ne)

Vstupné:

Zdarma

Další informace naleznete na webu Senátu Parlamentu ČR – ZDE.

Napsali o nás:

Restaurátorské práce v areálu Valdštejnského paláce, časopis Senát, 2/2000

Cena Europy Nostry pro Valdštejnský palác, časopis Senát, 3/2003